A t this writing, the cast of characters in the sexual harassment scandals that have been carpet-bombing the media continues to expand. Every day new women come forward to say they’ve had a bad experience. The scandals have touched scions of the right (Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly) and darlings of liberal elites (Al Franken, Charlie Rose). And in all the mess, in all the arguments about whose job it was to fix this situation, whether the burden was on men to stop harassing women (unlikely), or women to stop being so sensitive about men (unfair), one clear villain did emerge, a character in almost every truly awful story that emerged from the #MeToo moment: the non-disclosure agreement.

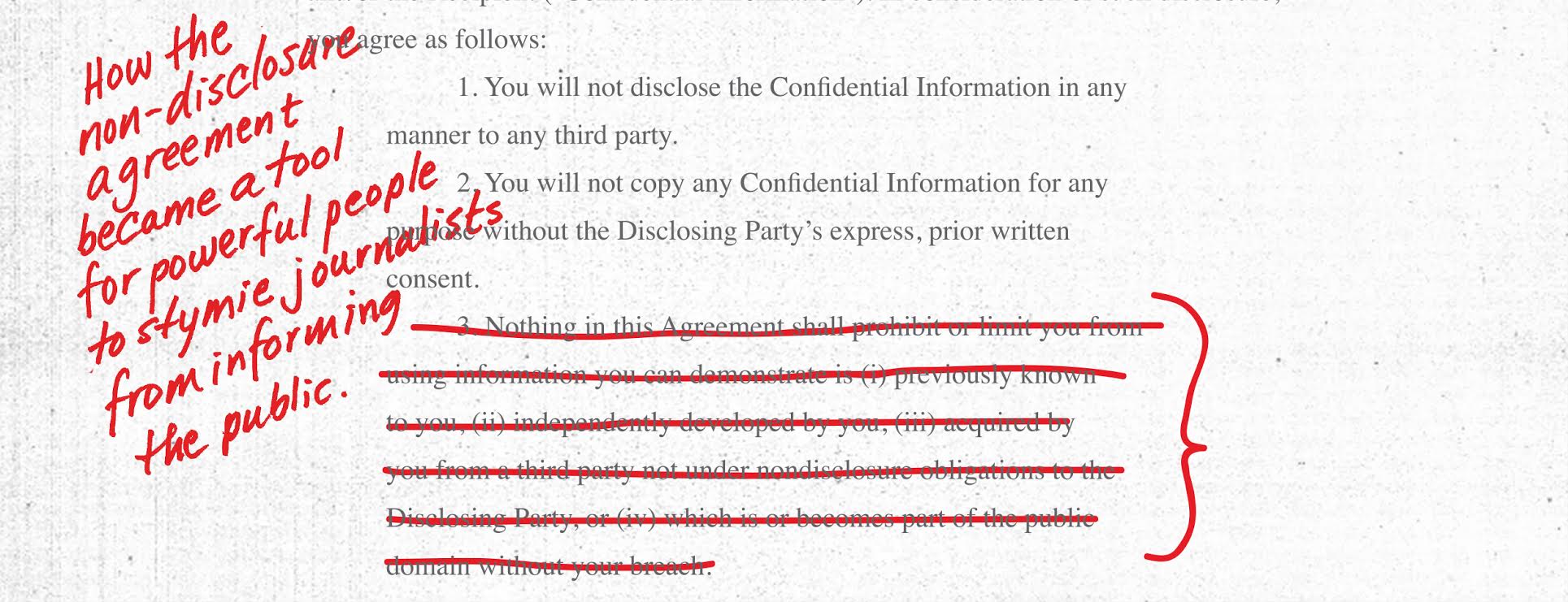

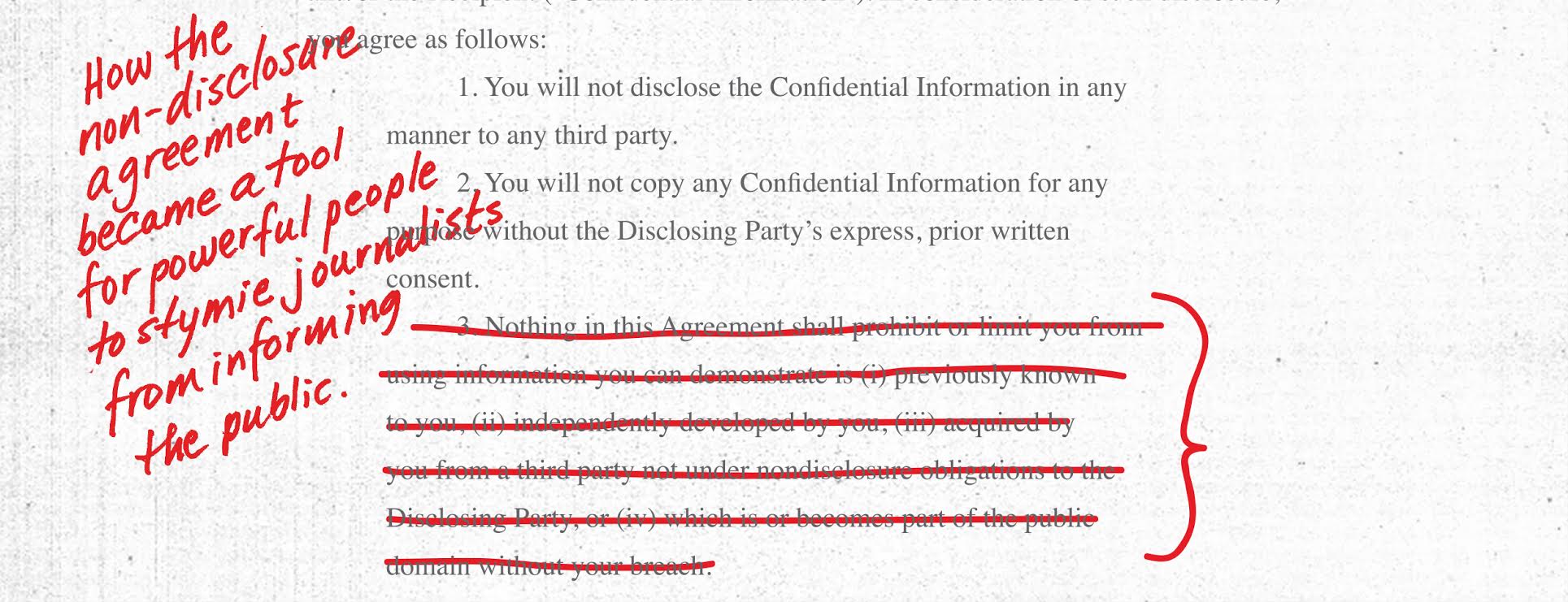

The reason many of these men felt protected from the consequences of their own bad behavior is largely the same reason many corporations are confident their embarrassing revelations will never come out: Once a quirk of the technology industry, non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) have proliferated across the business landscape, purportedly placing every secret, every item of misconduct out of public view—or more specifically outside of the view of some inquiring journalist who might want to expose a misdeed.

The outpouring of sexual misconduct allegations all began, really, when former Fox News anchor Gretchen Carlson filed suit against Roger Ailes in July 2016. Though she would later receive a reported $20 million settlement (which likely included a non-disclosure clause), news of her suit brought other women who had settled such claims out of the woodwork. Laurie Luhn, who had settled her sexual harassment claims against Ailes for about $3.15 million, was asked to sign what New York magazine characterized as a “settlement agreement with extensive non-disclosure provisions.” She said that after Carlson’s lawsuit was filed, she had decided to speak out anyway. “The truth shall set you free. Nothing else matters,” she said.

Still, it was not until reporting about Harvey Weinstein was published by The New York Times and The New Yorker that the issue of NDAs seemed to finally catch the attention of the public. Weinstein’s baroque efforts to prevent his victims from speaking had extended far beyond simple legalities, of course. Ronan Farrow would eventually report that Weinstein had hired a security agency staffed by ex-Mossad agents to dig up dirt on his accusers. All the same, it did seem that part of the fear that kept so many quiet was the threat of legal action against them. In his original story, Farrow quoted an actress who’d initially spoken on the record, then begged him to keep her out of it: “I’m so sorry,” she reportedly wrote. “The legal angle is coming at me, and I have no recourse.”

NDAs are enormously controversial, even within the legal community. From one vantage—say that of an exceptionally cautious lawyer, or an exceptionally frightened employee—keeping silent is thought necessary to avoid hefty financial penalties. Another view holds that NDAs are often unenforceable, most clearly if the activity meant to be kept secret is illegal, and that even where a court might uphold the agreement, a lot of potential plaintiffs don’t want to have to give the other side discovery on their bad behavior. But if you’re not as brave as, say, Rose McGowan, if you’re not a reporter, if you think you might have something to lose, you’ll probably obey the words on the paper. You’ll probably keep quiet even if you have something to say, out of sheer fear about the consequences. Companies rely on everyone’s lack of knowledge about just what confidentiality agreements are—and how easily they might ruin you.

Sign up for CJR 'sThere’s no clear origin story for the non-disclosure agreement, no Edison or Franklin who lays claim to the form. But a search of newspaper databases informs us that mentions of such agreements began popping up in the 1940s in the context of maritime law. Later, they began appearing more often at burgeoning tech firms like IBM. And in that context, NDAs kind of make sense. Tech companies have trade secrets to protect, proprietary algorithms they want to keep to themselves. Leaks by disloyal employees pose very real business risks.

By the 1970s, NDAs were popping up in new and surprising places. For example, during the House Select Committee on Assassinations’s investigation of the Kennedy and King assassinations in the late 1970s, The Washington Post reported that consultants working for the committee were asked to sign an NDA that forbade them to “indicate, divulge or acknowledge” that they even worked on the investigation while it was ongoing. It also asked these consultants to report to the House any efforts by a reporter to obtain information about the investigation. And while a few critics did seem to think the secrecy was excessive—“You’ve got to have this stuff subject to another point of view. The press has got to air it,” one said—in general the terms seem to have been accepted as necessary for the preservation of national security. After all, one of the entities the committee investigated was the Central Intelligence Agency itself.

It was only in the 1980s that the concept of non-disclosure began to creep into contracts of all kinds. It became a de rigueur provision in employment contracts for a certain kind of white collar job. And perhaps most crucially, it became a regular feature of legal settlement agreements. It was then that these “contracts of silence,” as one law review article termed the whole spectrum of NDA/non-disparagement/confidentiality clauses, really began to pose a problem for journalists. They became a barrier to some of the biggest stories of corporate misconduct out there. Most famously, an NDA intervened when Jeffrey Wigand, the tobacco industry whistleblower whose revelations about health risks consumed the news for weeks in the 1990s (and later became the basis for the Michael Mann movie The Insider), spoke to 60 Minutes in the fall of 1995.

Wigand, a former vice president of research and development at Brown & Williamson, had signed a confidentiality agreement as part of severance negotiations after he was fired in March of 1993. But he then began to work with 60 Minutes on its reporting about the industry’s efforts to conceal research done by Wigand among others on the harmful effects of smoking. And against the backdrop of an acquisition by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, and also because of the nature of Wigand’s work with the show—he was paid a consultant fee for part of it and CBS promised to indemnify him against any future suit from his employers—CBS’s in-house counsel raised the alarm that the network could be sued for “tortious interference” with his NDA. A version of the planned story aired, but without Wigand’s interview.

Once a quirk of the technology industry, non-disclosure agreements have proliferated across the business landscape, shielding misdeeds from public view.

A foofaraw ensued after Mike Wallace went on Charlie Rose’s show and criticized CBS’s decision to suppress the interview, saying, “We at 60 Minutes—and that’s about 100 of us who turn out this broadcast each week—are proud of working here and at CBS News, and so we were dismayed that the management at CBS had seen fit to give in to perceived threats of legal action against us by a tobacco industry giant.” The tape of Wigand’s interview languished for months before it finally aired in February 1996, after The Wall Street Journal published testimony Wigand had given in a lawsuit, which was thought to lift the potential threat.

In spite of the massive publicity around the case, only in legal academic circles did the Wigand case seem to occasion any kind of conversation about putting an end to “contracts of silence.” Because NDAs were relatively new, there were not a whole lot of court cases to go on, but many academics have theorized over the years that there ought to be some kind of exception built into the law. There were instances, they pointed out, bolstered by reporting, where the web of confidential settlements and other NDAs were covering up serious wrongdoing, such as the conduct of the Catholic Church in several sex abuse scandals. Confidential settlements had also, on occasion, been used to quiet plaintiffs who suffered harm from an environmental hazard, something other members of a community might want to have been made aware of. Over time, confidential settlements have been said to play a role in concealing, among other things, the dangers of silicone breast implants, the flaws in a kind of side-mounted gas tank used by GM, and toxic-waste leaks into rivers across America.

As a result of that relatively wonky discourse, about 20 states passed “sunshine-in-litigation” statutes that keep courts from enforcing NDAs in cases where some public hazard is at issue. Other states have instituted rule changes that have the same effect, prohibiting the court from approving, and thereby sealing, confidential settlements. Still other courts have local rules in which, in certain circumstances, confidentiality provisions are unenforceable. But the laws and the cases are piecemeal. And they don’t necessarily cover every kind of wrongdoing that non-disclosure agreements cover up. Like, say, sexual harassment.

Adam Schrader was laid off from The Dallas Morning News in early 2016. So when he was offered a job on Facebook’s trending news curation team a few months later, he took it, even though among the papers he had to sign was an NDA forbidding him from talking about his work for the company.

Schrader, like most journalists, isn’t too fond of NDAs. “We expect governmental and other companies to be transparent and forward with us with their practices and how they operate,” he says. So journalists can’t themselves turn around and claim a contract limits their right to be transparent about their own work. “I just don’t think that people who are expected to uphold the truth should be contractually obligated not to whenever it’s an important story that can impact millions of readers,” Schrader says.

But with the grimmest of journalism employment markets stretching out in front of him, he also badly needed a job. “I was offered a great salary. I had benefits. It was a New York job for a major social media company,” Schrader says. “That trending news module was actually highly trafficked, so you know, I felt like it was an important job to take. Regardless of the NDA.”

In fact, his attitude towards the NDA was pretty irrelevant. Like most prospective employees in America, Schrader didn’t have the bargaining power to propose taking $2,000 less in salary in exchange for dropping the NDA. “You offer that up, and the employers are not gonna hire you,” Schrader says. And he didn’t expect, when he was hired, that he’d ever need to break the agreement. He didn’t expect that anyone would ever be interested in the day-to-day of this new job of his.

Fast forward several months, and suddenly the Facebook trending news curation team had actually become news itself. Early in Schrader’s tenure, Gizmodo reported that the news curators were actively suppressing conservative links from the trending box. One of the sources was said to be someone within the curation team itself. Facebook, and other curators who subsequently went public, denied the report. But the idea that political bias was shaping Facebook’s coverage of the news quickly caught fire on conservative social media. Eventually, seeking to distance itself from journalism altogether, Facebook chose to fire the entire trending news curation team, including Schrader.

After his dismissal, Schrader talked to a few reporters, always anonymously. But the idea of remaining anonymous ate at him. As a reporter himself, he had mixed feelings about using anonymous sources. So in the fall of 2016, when Facebook’s fake news problem was drawing increasing scrutiny, he spoke out under his own name, filming a segment for Vice News Tonight that aired a week after the election. In the interview, Schrader talked about his concern, now that there were no humans fact-checking the trending news topics, that misleading news sites would be able to proliferate further. He tried to explain how news curation actually worked, and that it involved a lot more reporting and actual journalism than you might expect, all in an attempt to verify (or debunk) wilder viral stories. He said he worried that Mark Zuckerberg was in “denial” about Facebook being a news product. And perhaps most importantly, Schrader acknowledged that he was not supposed to be talking about any of this, “I’m not scared of Facebook or violating my NDA because, you know, I think that it’s more important to get the message out there that Facebook needs to get its act together and get in the game.”

Companies rely on people’s lack of knowledge about confidentiality agreements—and how easily they might ruin you.

In the aftermath, Schrader says, he did not worry too much about being sued. “It’s not like I was speaking negatively about the company,” he says. “Everything that I spoke out about was factual. I mean, people just really wanted to know what we did.” He never heard from Facebook itself, though he noticed, suddenly, that senior managers at Facebook were looking at his LinkedIn profile. That “did make me a little bit nervous,” Schrader concedes, but he wasn’t sure it would be so bad if the thing went to court.

He did get a letter from BCforward, the contracting agency which paid him, notifying him that he was in breach of the agreement. It had frightening language about how he could be on the hook for large sums of money. But, again like most journalists, Schrader didn’t really have any assets such a suit could claim. “All right sue me, you can have my few hundred dollar laptop, like great. Enjoy it,” he jokes to me. “Please take my car, I can’t afford it anymore.” No lawsuit ever did materialize.

Of course, the risk of breaking any contract is an individual calculation, and anyone thinking of doing it ought to talk to an attorney. One lawyer who knows a lot about this is Neil Mullin of Smith Mullin in Montclair, New Jersey, who represented Gretchen Carlson against Fox News. A gregarious speaker with a thick Jersey accent, Mullin has negotiated a lot of confidentiality clauses in sexual harassment cases and corporate whistleblower cases alike in his plaintiff-focused career. Corporations insist on them, he tells me, “often with monetary penalties. I signed an agreement about a year ago with a $750,000 penalty for each single violation of the confidentiality clause.”

Plaintiffs, on the other hand, rarely seek them out. “I have found that our clients resent these clauses right from the beginning,” Mullin says. “They don’t want them. They hate them. They would love to break them.” And some do, feeling driven to inform the public. In the Ailes case, there was Luhn; in the Weinstein case, though machinations at NBC have obscured the precise development of the Ronan Farrow end of the story, it’s clear that McGowan spoke in spite of believing at the time that she was under an NDA. (In the summer of 2017, she discovered her original settlement with Weinstein did not contain a confidentiality clause.) Indeed, breaking an NDA has become a badge of honor. When Zelda Perkins, a former Weinstein assistant who’d witnessed him assaulting a colleague, came forward, she specifically told everyone she was doing so in spite of a confidentiality clause in her settlement. A group of former employees of The Weinstein Company who issued a statement soon after the allegations were made public proudly proclaimed they were in breach, too. “We know that in writing this we are in open breach of the non-disclosure agreements in our contracts. But our former boss is in open violation of his contract with us—the employees—to create a safe place for us to work,” their statement read.

But people who are considering speaking to a reporter in spite of a confidentiality agreement, Mullin tells me, should be afraid. Though there are, he says, decisions out there that limit the effect of NDAs in the event of illegal activity, the cases are not consistent. And he says he’d never advise a client to break any relevant agreement. “I think journalists should not take this lightly,” he tells me. “If you persuade a lay person to breach a confidentiality agreement, you’re putting them in grave financial danger.”

Mullin believes that journalistic organizations ought to be prepared to support and even indemnify a victim for any legal fees they might incur for lawsuits afterwards, much as CBS once offered to indemnify Jeffrey Wigand. And he believes this, Mullin says, even though he and his law partner (and also his wife) Nancy Erika Smith, are passionately opposed to NDAs. “We believe strongly that this practice should end, even if it means that it’s harder to settle cases, more cases go to trial,” Mullin says. “In the long run, it’s good for women. It’s bad for predators. Bad for patriarchs and sexists in the workplace.”

“I have found that our clients resent these [confidentiality] clauses right from the beginning,” says Neil Mullin, an attorney who represents plaintiffs in sexual harassment cases. “They don’t want them. They hate them. They would love to break them.”

Still, while NDAs remain enforceable by courts, Mullin has also made clear he will fight what he sees as the good fight with every tool in his arsenal—including, in what some might see as a twist, confidentiality and non-disparagement provisions in settlements he has negotiated. In early December, he and Smith filed a lawsuit on behalf of Rachel Witlieb Bernstein, one of the women who’d settled a sexual harassment claim against former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly, all the way back in 2002. The settlement contained non-disparagement and confidentiality clauses.

Bernstein, the lawsuit complains, has kept her end of the deal: She’s never spoken publicly about whatever experience it was that she had with O’Reilly. Her name was mentioned in an April 2017 article in The New York Times, which listed her as among the women who had received settlements from Fox News relating to O’Reilly’s conduct that totaled $13 million. (Subsequent reporting raised that figure to $45 million.) But Bernstein says she was not the source of the information in that story.

Meanwhile, since he was ousted in April, O’Reilly has made frequent statements to news outlets in which he complains that the charges against him are untrue and ideologically motivated. “No one was mistreated on my watch,” he insisted to The Hollywood Reporter. He also says that while he was at Fox News, no complaints about him were ever brought to human resources. Mullin and Smith say this sort of statement—which O’Reilly has made again and again—disparages their client. The complaint makes claims of breach of contract, defamation, and tortious interference with a business contract.

“I don’t like non-disclosure agreements, but if you impose them on my clients, you damn well better obey your side of the deal,” Mullin says. “I’m put in this position of enforcing an agreement, but I’m enforcing it because it’s been violated unilaterally. That’s not tolerable. That’s not justice.”

A lot of people seem to agree with him, including lawmakers in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, who have introduced bills that would ban NDAs in cases involving sexual harassment. But the solution is a patchwork one. And the fact remains that for the foreseeable future, nearly every one of these cases will continue to feature an NDA in a starring role.

Michelle Dean is the 2017 recipient of the National Book Critics Circle’s Balakian Citation for Excellence in Book Reviewing and has written for Wired, The New Republic, and The New York Times Magazine. Her first book, Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion, will be published in April 2018.